The importance of new online and social media in influencing voters’ perceptions and behaviour has risen rapidly over recent election cycles. Social media now plays a key role in amplifying messages placed in traditional media and in influencing what traditional broadcast and print media covers during election campaigns. The potential for narrowly targeted advertising, as well as the “organic reach” achieved when content is voluntarily shared, can make it a highly cost-effective form of political communication.

The level of online campaigning and advertising in this campaign was unprecedented. Labour declared its central focus to be “making viral persuasive content – bypassing the media and breaking out of the bubble”.[109] Significant resource was dedicated to this strategy:

Successes were claimed by Labour’s digital teams, including:

However, the evidence we have received shows that overall the Conservatives were far more effective in this arena.

In preparing this chapter, we were able to draw on

Research conducted for this Commission by Valent Projects found the Conservatives were determined to improve on their 2017 campaign, and invested in infrastructure, skills and expertise, developing a comprehensive and multi-faceted strategy to beat us next time.

Key elements of this included:

Over the summer, and well ahead of the election, the Conservative Party was running hundreds of ads with slight differences in colour, wording and even using different emojis. Although Facebook’s portal for political advertising doesn’t show what criteria advertisers are using to identify those they want to reach, the content of the ads and relatively small budgets (often under £100) suggests they were being targeted at individual constituencies.

By using the statistical feedback provided to ad buyers on the performance of ads, the near £100,000 that the Conservative Party spent on the ads in the summer of 2019 would have bought immense amounts of constituency-level data on what messages work best with different groups of people, based on their ages, gender, area of work and political affiliation.[117]

By the time the election campaign began, the Conservatives were able to capitalise on the information they had accumulated. Their ads have been described as “laser-guided” – using neon graphics and up-tempo music to push a “Get Brexit Done” message to 300,000 men under 34; classical music, softer colours and additional pledges on the NHS and crime for 350,000 women over 55.[118] Towards the end of the campaign, the Conservatives ramped up its Facebook advertising, with 7,000 ads in early December – 90 per cent of which contained misleading claims, according to analysis by First Draft.

Clearly this approach proved highly effective, particularly in exploiting negative perceptions of Labour’s Leader, with many candidates and campaigners reporting the impact of a surge in negative online campaigning in the final week of the campaign.

This was reinforced by “outrider” activities. Monitoring group “Who Targets Me” identified nine non-party groups that spent around £300,000 on Facebook ads in the month before the poll.[119]

Local groups may also have had an important influence. For example, research conducted for this Commission by Centre for Countering Digital Hate identified a Facebook Group in Dudley which built followers by posting local news which hosted a large amount of anti-Labour and anti-Jeremy Corbyn content, with “comments” being used to organise protests against Jeremy Corbyn’s visit to a local pensioners’ club during the campaign; this story later appeared in The Sun, with the headline “Jeremy Corbyn heckled as ‘dirty IRA scum’ when he arrives in key Dudley marginal.”[120] The account hasn’t posted since 12 December 2019.[121]

Reviews we commissioned from Valent Projects, CCDH and Common Knowledge show that, despite all the activity and resources invested, Labour’s online campaign fell well short of the Conservatives in this election. The primary source of this shortcoming was the absence of strategic integration and structured innovation, identified as a fundamental organisational and cultural weakness in the previous chapter.

Labour lacked an imaginative strategy for digital campaigning. Online output was siloed off from broader strategy and communications, instead of being centrally integrated. The Party’s social media channels simply became an additional broadcast platform, rather than a dynamic and responsive tool for targeting, engaging and persuading key groups of voters. Our communications with the voters remained one rather than two way, seriously limiting their effectiveness.

Valent Projects and CCDH found a lack of focus and – reflecting broader criticisms of Labour’s communications effort – no consistent messaging strategy. The Conservatives’ core message “Get Brexit Done” lent itself easily to the “distributed spin” approach, whereby supporters can pick up and disseminate frames and messages and help to shape audiences’ views of the campaign and related news stories. By contrast, the proliferation of different messages and policies in Labour’s online campaign made it harder for online supporters to find a core message to reinforce, and made it easier for them to get diverted into less helpful activities such as criticising the BBC’s election coverage.[122]

As in other areas, Labour was not well-prepared for the online campaign when it began. Valent Projects’ research shows that the Conservatives began using Facebook to stress test messaging and imagery in the summer, as soon as Boris Johnson was elected as their Leader. Labour only began similar testing once the election had been called. In August, independent online monitoring group “Who Targets Me” noted that, while the Conservatives were investing heavily in data collection and attack ads, Labour’s strategy was “unclear” and “notably less disciplined”. [123]

According to the findings of the reviews we commissioned, the fast-moving nature of online campaigning saw Labour’s collective levels of skill and understanding fall well behind the curve. Labour does not have enough politicians, staff or activists up-to-speed on digital campaign techniques – something the Conservatives addressed by handing most of it over to a commercial consultancy.

Symptomatic weaknesses included:

Labour’s confused messaging was compounded by the number of people involved in producing or approving content without any shared framework or strategy. It’s clear from all submissions that little thought was given as to how different platforms, channels and messengers across the Party could be used effectively to reach different audiences, both members and voters.

An organogram prepared for this Review by Common Knowledge shows multiple social media teams across the Party, without clear lines of communication or coordination with each other. The Leader’s Office established a separate social media team of eight, which had no clear relationships to the team in HQ. This led to internal battles, leaked reports and frustration on both sides.[125] The involvement of an agency in message testing further complicated the split responsibilities.

The Commission heard that the Party’s digital campaign team were held back by a lack of creative freedom, and that cumbersome sign-off processes were a problem, despite it being public knowledge that the Conservatives knew a key weakness of their 2017 digital campaign had been slow and unresponsive decision-making.[126] We were told there was a significant time lag between social media content being produced and it then being shared on the Party’s social media channels, reducing Labour’s ability to manoeuvre in a fast-moving online environment.

Problems of leadership and coordination at the centre were compounded by insufficient guidance, support and leadership given to Parliamentary Candidates and CLPs, who were left to devise their own strategies, without professional support or a framework of consistent messaging.

Labour Party staff certainly did their best – for example, the Campaign Office for Rosie Duffield’s successful campaign in Canterbury “welcomed the exceptional support with social media from the Regional Office team”.[127]

However, lack of coordination from the centre meant the level of social media support available to candidates varied, depending on the resource available to regions and nations. The digital campaign was highly centralised, with little resource given to Regional Offices for content production and minimal training or support for candidates to produce content. Many Labour candidates and activists did not know how to use the Promote tool, or found it difficult and cumbersome. Candidates often did not understand how to use Facebook effectively, let alone shoot quality videos or create shareable content. One defeated MP complained that the Party did not “inform or consult us on what Facebook/social media they were directing and to which voters, so our own could complement these”.[128] Another told us “the internal mechanics of getting social media to work was terrible in 2017 and 2019… Real difficulties with Promote – we weren’t able to use it in either election”.

This contrasts strongly with the effective use by the Conservatives of a professional consultancy to support candidates’ social media campaigning in key constituencies, which the review we commissioned from Valent Projects showed to be a key ingredient in the Conservatives’ online success.

Labour-friendly organisations and individuals with large social media followings clearly played a role in engaging and mobilising Labour activists and supporters.

Momentum, for example, believe they “significantly outperformed the Party in terms of member engagement and mobilisation while also filling substantial gaps in Labour’s campaign”. This included what they saw as a “dramatically” improved social media performance, including:

However, it is unclear what effect many Labour-friendly organisations and individuals had in broadening Labour’s support. One digital consultant commented: “While organically Labour did really well…most of the views and shares came from people who were already going to vote Labour.”[129]

The review conducted for us by CCDH showed that many alternative media sources have declined in reach since the 2017 election, partly due to changes in Facebook’s newsfeed algorithms, which gave greater prominence to content posted by friends and family and discussions taking place within Facebook groups or forums, and less to “followed” pages.[130]

These outlets also tend to operate in silos, focused on internal Labour Party processes and debates taking place within “the Left”. They were not focused on reaching across political divides, to target particular demographic or interest groups, or undecided voters.

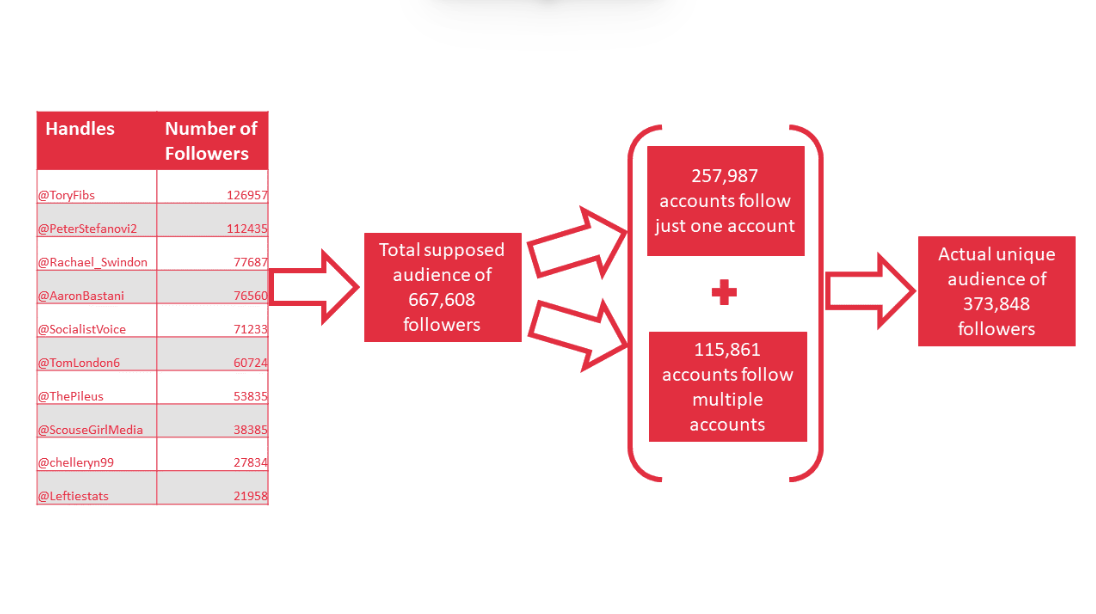

We analysed ten of the most active Labour supporting Twitter accounts: in total, these accounts collectively have 667,600 followers, but their unique reach is half of this, as they collectively only have 373,800 unique followers. Of those 373,800 unique followers: 257,000 follow just one of the ten accounts, while 115,800 follow multiple accounts. This shows that the large following of many “left-wing” Twitter accounts could actually be the result of a much smaller number of accounts just following each other, resulting in little reach beyond those who are already supportive of Labour.[131]

Figure 42: Twitter audiences of “Left outrider” accounts

As indicated above, there was not a strong strategy for creating content for supporters that would likely be picked up and shared further to broader audiences. Occasions when Labour’s Twitter supporters reached the widest audiences were often in the context of issues unlikely to win over new supporters, such as disagreements over the Party’s handing of anti-Semitism or criticism of the BBC’s reporting of the election.[132]